Before delving into Ben Wheatley’s In the Earth, we must take a little detour to focus on the figure of Roger Corman. Widely known for his prolific career, it would be a shame to limit his figure to that of a director and producer with a catalogue filled with B-movies in which monsters run amok. His philosophy for making films could be seen as some kind of compulsion, as he was able to complete a feature in a matter of weeks before moving to the next one (he even managed to shoot the 1960 version of The Little Shop of Horrors in two days and one night). Keen on making the most of each and every penny on the budget -which usually would be more or less the same as that of a fancy wedding video-, Corman would reuse shots in various films, and even used the same locations to film scenes for different productions at the same time.

His impact on popular culture -which to fully cover might need its own monograph- is not only limited to films like The Wild Angels, Machine Gun Kelly, X The Man with the X-Ray Eyes, and his Edgar Allan Poe adaptations with Vincent Price (among many others to mention), as he has also been a mentor figure for people like Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Jonathan Demme, Ron Howard, Peter Bogdanovich, Joe Dante, Jack Nicholson and Robert De Niro among others. Furthermore, his fast-paced style of filmmaking and his ability not only to adapt, but to bloom with highly limited budgets, allowed him to shift from one genre and trend to another, enabling him to create films that were inspired by that specific moment’s zeitgeist. An example of this is War of the Satellites , a 1958 film in which people from Earth have to fight “unkown forces” after a satellite was launched into space. Corman spent around eight weeks since the conception of the film to have a final product ready to be seen in the big screen, motivated by the fact that the society of that time had their eyes set on the Space Race, lead by the Russians and the Sputnik.

This capacity to adapt to the changing tastes of the audience meant that Corman has managed to have a diverse and original career that resulted in a long-lasting influence that still permeates in today’s society despite the fact that he has always been faithful to himself and his style. This idea of marching at the rhythm of your own drum can have the result of being relegated to the fringes of Hollywood. However, being independent and outside of the system is not necessarily a bad thing on itself, as one of the benefits of being an outsider is that as those who are in do not pay that much attention to those who are not. Not only you have less restrictions, but also there are no big expectations to fulfill, no big budgets to justify, no box office to pay attention to, no big stars with a different vision of the film they want to impose, less studio interference and so on.

The idea of a director starting out with small, independent films to then move to bigger -and allegedly- better projects is a misconception, as has been demonstrated with filmmakers jumping to direct a tentpole film, only to see their artistry crushed by the short-sightedness of a studio wishing to cash in. Crafting a film with passion and talent to compensate for the lack of big names or limitless resources is one of the less adulterated forms of cinema, as all that is on the screen -for better or worse- is only the vision of those behind the cameras, the dreams of those whose fascination with films is rooted deep inside them, and one of those people is Ben Wheatley.

Starting his career with commercials and short films, he made his feature length debut with Down Terrace, a kitchen sink black comedy he shot in eight days (even using a stopwatch in order to maximize the time they had) with a budget of around £6000. Despite having a bigger budget in his next projects, his films were still independent, meaning that he managed to fully translate his vision to the screen with not a great deal of interference from a studio. It is in these years that Wheatley made a name for himself by creating films that are clearly his own. Whether we get trapped by the tense sense of threat that lurks in every moment of Kill List, become the travel companion/witnesses of the central couple and their crimes in the darkly comedic Sightseers, or get lost with the characters of the nightmarishly hallucinatory A Field in England, we know we are watching a film directed by Ben Wheatley. No matter the different genres, as his universe is shaped by off-kilter characters, unpredictability and a no-nonsense attitude that, in combination with a certain rawness makes for a much powerful viewing experience.

After the critical success of those films he directed High Rise, Free Fire (produced by one of those directors inspired by Corman, none other than Martin Scorsese) and produced films like Peter Strickland’s In Fabric. Here, not only he was able to have access to a bigger budget, but also to more well-known actors like Tom Hiddleston, Brie Larson, Jeremy Irons or Elisabeth Moss. Some time later he shot Happy New Year, Colin Burstead, a much smaller project which, despite being slightly underseen, can be considered as a balance after his two bigger films to date. Considering that last year Netflix released his remake of Rebecca and that his next film is slated to be Meg 2 -the sequel to the film in which Jason Statham punched a humungous shark-, In the Earth feels like a welcoming and necessary return to his roots (pun intended) for Wheatley.

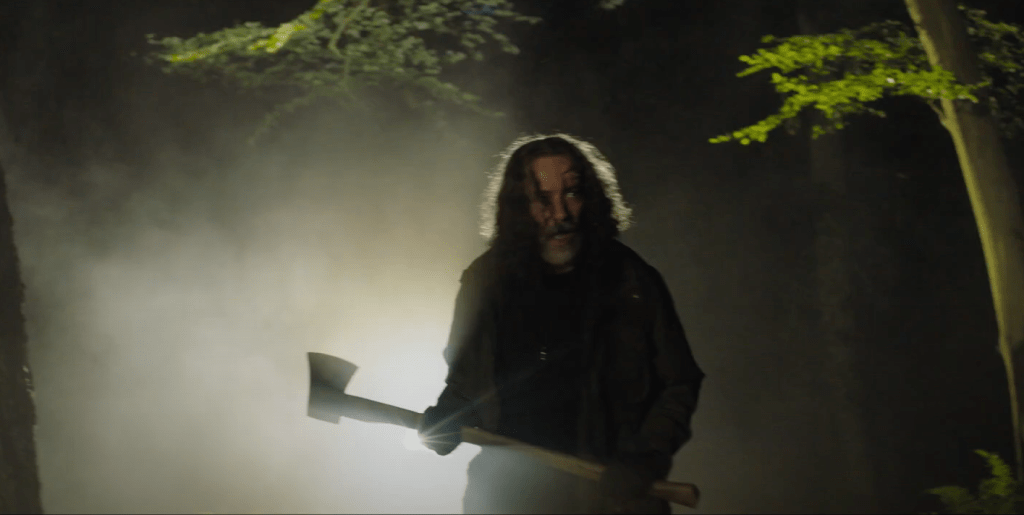

Directed under the restrictions of the Covid-19 lockdown, the film is centered on a couple of scientists -played by Joel Fry and Ellora Torchia- who find themselves lost in the middle of the forest after they had set off on a rutinary test. However, it is not too long before things start to get hairy for the central duo as they find themselves running away from an axe wielding man -Reece Shearsmith-, before meeting another scientist played by Hayley Squires. The -minimal- plot is not used for a more conventional horror film, but, instead is used to explore how intrinsic to our nature myths might be, to the extreme of becoming obsessions. It is approximately 30 minutes after the beginning of In the Earth when we perceive that Wheatley is firing up on all cylinders, as the somewhat minimalistic start of the film is left behind to submerge the audience on a chillingly hallucinatory trip in which is also quite hard not to feel close to the anguish the protagonists experience, partly due to the fact that we have been introduced to a pair of characters -albeit not too developed- who exist in a reality closer to ours, to whom we can establish a connection, and whose lives are put at stake in a daunting fight for survival.

It could be impossible not to have in mind the idea that this film feels like perfect companion to A Field in England, arguably Wheatley’s most celebrated film to date. Aside from the fact that Reece Shearsmith was also in A Field in England, in which he gave another masterfully haunting performance that could carry the entire picture -or any other for that matter- on his shoulders. As in that film, Wheatley -who is also the editor here- makes use of the trippy imaginery in conjunction with a misteriously atmospheric score by Clint Mansell -replacing the soundtrack by Jim Williams- to take the audience on a journey to experience an unfamiliar psychedelic dimension in a way that would make Alejandro Jodorowsky and Timothy Leary proud.

Low on the list of problems people have to worry about is the dilemma that creators could be facing, whether to create a world in which Covid 19 exists or set their fictional realms in a divergent reality where no global pandemic has existed as of recently. Films and TV shows inspired by Covid 19 have already been made, and probably once the dust is settled, more will be made.

In the Earth is a great film, but not as a result of its realistic portrayal of a world infected by a virus; that was never its initial mission -this also means that, as it is not intending to be a reflection of this period, it might easily stand the test of time-. It is a great film because here Wheatley’s skills and devotion to cinema are not focused on showing us a reality similar to the one we have now -with all characters in Zoom meetings and with all those badly framed shots we find in Locked Down-, here that familiar context is used only as a starting point to make the audience feel more comfortable, before being dragged to a natural realm in which is impossible not to feel as if you were lost and trapped. As happened with a great deal of the pictures in Roger Corman’s catalogue, Ben Wheatley has crafted a memorable, timely, little film that triumphs in spite of all the limitations, probably as a result of ingenuity and sheer passion for filmmaking.

You must be logged in to post a comment.