“I have a very strong sense of history and I don’t judge myself on the basis of my contemporaries but on the basis of 20,000 films made, 6,000 of which I’ve seen. I judge myself against the directors I admire — Hawks, Lubitsch, Buster Keaton, Welles, Ford, Renoir, Hitchcock. I certainly don’t think I’m anywhere near as good as they are, but I think I’m pretty good.” With these words, Peter Bogdanovich described himself as a director to the New York Times in 1971 after the success of The Last Picture Show and the release of a documentary entitled Directed by John Ford, homaging the figure of the legendary western director.

Bogdanovich made no effort to hide his pride, after all, he had successfully jumped from being a critic, journalist and film curator -creating retrospectives of his admired directors for museums like the MoMA- to a director with a promising career ahead of him. Indeed it appeared he was headed for Hollywood glory after the acclaim obtained by The Last Picture Show -film nominated to 8 Oscars, amongst them he received nominations for Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay-, What’s Up, Doc? and Paper Moon. However, his career took a dive with three consecutive critical and commercial fiascos (Daisy Miller, At Long Last Love and Nickelodeon), which led him to take a few years off.

Obviously, he was not going to give up easily, and thus he returned in 1979 with Saint Jack, followed two years later by They All Laughed. Both these films were better received, and it seemed as if his career was going to return to the promising path it initially had. Except that it did not.

Dorothy Stratten, a Playboy model and actress with whom he was having a relationship at the time she appeared in They All Laughed, was murdered by her estranged husband. This forced Bogdanovich to -again- step aside from directing for a few years, focusing instead on writing The Killing of the Unicorn, a memoir on Stratten in which he took a swipe at Hugh Hefner and Playboy for the way in which they mistreated women.

Finantially ruined and with an intermittent career that, sadly, was not living up to its initial potential, Bogdanovich continued to work, directing films such as Mask (in 1985) -his last critical and commercial success-, or She’s Funny That Way in 2014 -based on an old script written by himself and his former wife, Louise Stratten, Dorothy Stratten’s sister-. In addition, he also acted in some episodes of The Sopranos -he had studied acting earlier in his life and had brief roles in some films, including some of his own-, oversaw the completion of The Other Side of the Wind -Orson Welles’ last film-, and directed documentaries about Tom Petty – Runnin’ Down a Dream (for which he received a Grammy for Best Music Film), and another one on the figure of Buster Keaton, The Great Buster, back in 2018.

The fact that his documentary on Keaton was the last feature he directed before his demise in early 2022, puts a fitting end to his directorial career by paying homage to a filmmaker he admired, demonstrating his nostalgia for a golden period of Hollywood that was long gone. Whether you enjoy his films or not, it is difficult to argue that Bogdanovich’s eagerness to look back at the classics instead of wondering about the future of cinema (unlike people like Coppola or Spielberg did at the time), has been essential to keep the old days of Hollywood alive, as Scorsese put it “No one makes old movies better than Bogdanovich”.

Before his passion made him a fundamental figure for American cinema in the 1970’s, it caught the attention of Roger Corman, a filmmaker whose devotion to the art has helped shaping popular culture and has discovered talents such as Scorsese, Coppola, Jonathan Demme, Ron Howard, Joe Dante, Jack Nicholson and Robert De Niro, among others. Corman took Bogdanovich under his wing and gave him the possibility to break his teeth by working with Boris Karloff -in one of his last features- in any film he wanted, and the final result was Targets.

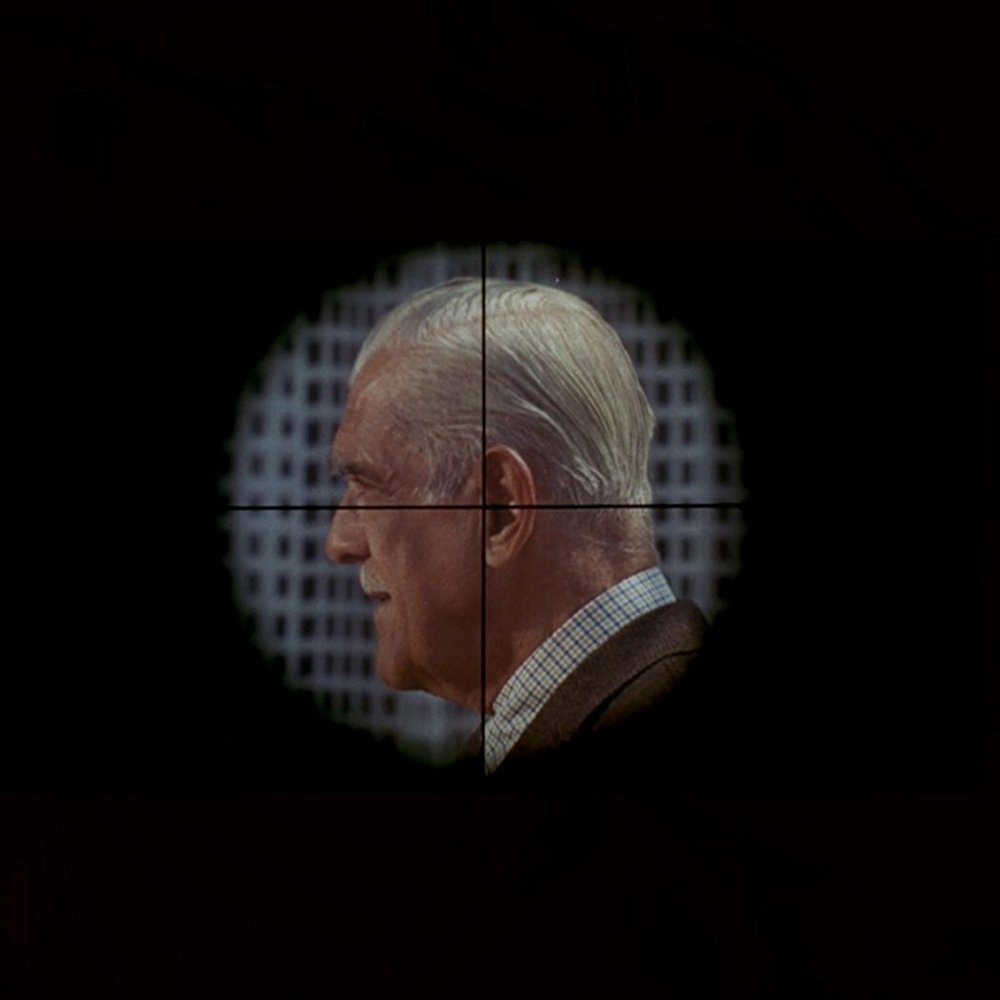

Written by Bogdanovich -and an uncredited Samuel Fuller-, Targets is a film that consists of two apparently isolated plots that slowly end up colliding in a tense finale. On the one hand, we have an almost autobiographical story of an ageing horror star, Byron Orlok -played with a mix of solemn aplomb and a sweet sense of nostalgia by Karloff- who suddenly announces he is retiring (against the will of the studio and of a young director, played by Bogdanovich), as he has become fed up with real-life violence, which he argues has overcome that of his own films. On the other hand, we are introduced to a quiet, respectable, everyday American citizen, named Bobby Thompson -played with an creepy aura of normality by Tim O’Kelly-, a man who happens to collect guns and who appears to be minutes away from becoming insane.

Bogdanovich cleverly contrasts the two stories -an embittered horror star who desires to leave all the violence behind and retire to a peaceful existence, and a regular citizen whose life is secretly disturbing- as the basis for Targets, and, as whole, the film manages to put forward the issue of a society that has become so accustomed to violence that the image of Orlok -technically Karloff- in Corman’s The Terror does not scare them whatsoever, as they are used to suffering real life attacks in supermarkets, schools, and indeed cinemas.

However, neither of the two narratives collide until the end. During most of Targets, we jump back and forth between Orlok and Thompson with no rhyme nor reason, and the issue is that the resulting film feels slightly disjointed, as if it had originally started life as two different pictures that were then put together in the edit room to save costs -something that is not as bonkers as it might appear, giving that Corman was behind the production and, as a matter of fact, Karloff happened to owe the studio two days of work-.

Nevertheless, Bogdanovich manages to make Targets a film that, as many of Corman films used to do, feels timely for its era -it had to be postponed due to the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and of Robert F. Kennedy-, whilst it still feels necessary today, given that violence keeps being an uncontrollable danger which we are -sadly- increasingly used to watching on the daily news, surpassing the brutality of current films (such as the heart-wrenching If Anything Happens I Love You). While it is true that it could have been more effective without Karloff’s scenes, the film still manages to convey its message in a way that does not feel extremely exploitative.

Aside from being a solid debut and a homage to Karloff’s career -to the point that he watches himself in Howard Hawks’ The Criminal Code-, Targets is a look back to a bygone era through the eyes of Bogdanovich, a nostalgic cinephile who was about to show the world what he was capable of.

You must be logged in to post a comment.