Back in 2012, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (based on a novel by Jonathan Safron Foer), starring Sandra Bullock, Tom Hanks, Max Von Sydow, Viola Davis, Jeffrey Wright and John Goodman, among others, premiered to a lukewarm reception by critics and audience alike. Among the reviews the film got, there is one by the master Roger Ebert that was constantly in my mind as I watched Worth. Ebert started his 21/2 stars review of Stephen Daldry’s film by saying that “No movie has ever been able to provide a catharsis for the Holocaust, and I suspect none will ever be able to provide one for 9/11. Such subjects overwhelm art. The artist’s usual tactic is to center on individuals whose lives are a rebuke to the tragedy. They sidestep the actual event and focus on a parallel event that ends happily, giving us a sentimental reason to find consolation. That is small comfort to the dead.”

Twenty years ago, regardless of your age, gender, nationality or profession, an image was probably cast on your mind forever. That day was one like many others before and many others to come. Maybe in your life something remarkable had happened, or maybe you were expecting something to materialize. However, none of that mattered as the world came to a sudden halt, and in televisions everywhere the horrific image of a plane crashing onto one of the Twin Towers repeated -as the news have the habit of looping the images ad nauseam-. Nobody knew what was happening -let’s not forget all of that took place in the days before we were glued to a device that allowed us easy access to the internet- and then the second plane crashed, making everybody gasp and remain in silence with no coherent thoughts. Nobody is ready to handle a tragedy of that scale, it did not matter that we had seen The White House destroyed on Independence Day, as fiction can be wilder and crazier than reality, but, at the end of the day, it is all make believe.

Filmmakers -as well as artists of other disciplines- were inspired by that hideous act of terrorism and they explored the lives of those who perished, the aftermath and/or propose a way that can be used to try and release all the emotions we all had. However, handling the effects of a tragedy of that magnitude in a way that feels human, solemn and can help the audience deal with their emotions is no easy feat, and most of the films have tackle 9/11 in a similar fashion, i.e. by following the aftermath of the attack in the lives of those who lost someone (like in the aforementioned Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close or in Reign Over Me), or, as in the case of Oliver Stone’s World Trade Center, focusing on the first responders.

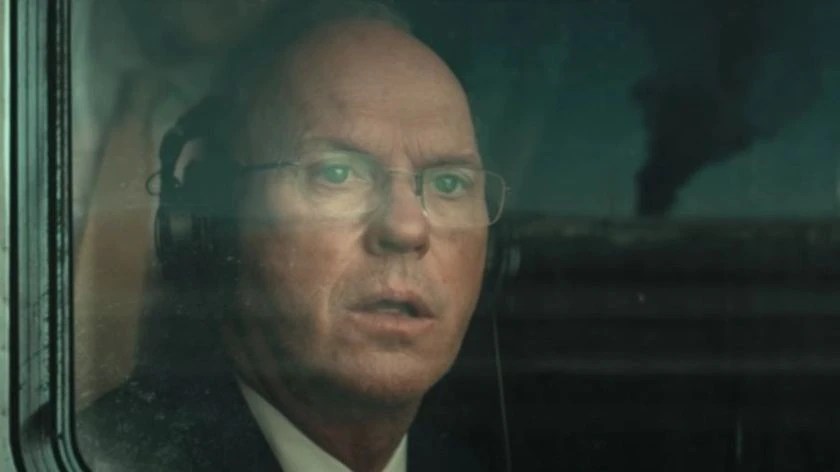

Worth, directed by Sara Colangelo centers its plot on the real figure of Ken Feinberg, played by Michael Keaton, the person in charge of the task of coming up with a specific amount of money dedicated to act as a compensation for the relatives of those who passed away on the World Trade Center. In other words, Keaton’s character has been handed the task of finding out how much a life is worth, therefore, in order to do so, he achieves a team and, trying to be as fair as possible, they start to figure out how much is the correct amount. The film avoids treating those related with the victims of 9/11 as mere numbers and it does manage to portray some touching testimonies in the way of interviews between the relatives and some members of Keaton’s team -lead by the always reliable Amy Ryan, as Feinberg’s partner Camille Biros-. These testimonies represent the most human part of Worth, partly because they are played by a selection of actors and actresses whose less familiar faces made their interventions much more believable than if they had been played by more recognizable names. The negative side here is that, despite the poignancy of those moments, they are relegated to the margins of the story, as we spend the majority of the film accompanying Keaton’s character, who tries to remain at a certain distance, in order to avoid being influenced.

While it is true that it deals with an incredibly difficult task -i.e. finding out the value of human life-, the film does not manage to completely transmit that in a way that feels really meaningful, transformative or poignant. Instead, by following mostly Feinberg and his team, the film wanders on familiar territory (yes, there are moments of doubt; yes there are moments in which the characters are sad and it seems impossible to achieve their task; yes, there are people in power with hidden interests; yes, there is a deadline that gets closer and closer), meaning that its conventionality does not do a lot to instill life to the real people behind the characters. All of this is not to say that the role played by the characters of Keaton, Ryan, and the rest of their team, is meaningless or that their story should not be told. Furthermore, neither Keaton nor Ryan are bad in their roles; quite the contrary as both give understated and believable performances that hold the film toghether, despite not having the most developed of characters.

The issue of having an unbalanced film with regards to telling the story of Feinberg, whilst giving the importance that is due to the families, is clearly exemplified with the role played by Stanley Tucci. Obviously the issue is not related with his performance, as it is almost impossible to see a bad performance from him; the problem lies on the fact that, although he plays a widower and one of the biggest opponents to the formula proposed by Feinberg -he went as far as creating a website titled “Fix the Fund”-, he barely appears in two or three moments throughout the film. One might think that somewhere there is a film that is much more rounded and emotional, one that can feel more human and yet subtle, as the scene in which Tucci goes over the contents of his fridge and sees a tupperware with a label written by his wife.

To summarize why Worth does not fully work, we could go back to the other time Keaton and Tucci were in the same film (although they did not share any scene). Tom McCarthy’s Spotlight (film also produced by Michael Sugar, one of the producers of Worth) was a critical success as it managed to honour the victims, handle the thorny issue of abuse by the church, whilst being also a love letter to journalism, thanks to the script written by McCarthy and Josh Singer and a direction that felt more confident and less by-the-numbers. Worth, on the other hand, does not strike a balance between giving a voice to the victims and their families and giving value to the hard task that Ken Feinberg and Camille Biros achieved.

Despite pondering on how much a life is actually worth, by the end of the film we do not feel as if we have an answer -though they did manage to strike a deal and solve the issues with the fund-, and this is a shame, as with all its good intentions and solid performances, Worth is a formulaic film that falls on familiar territory that, like the money given to the families, serves a honorable purpose though feels like a necessary, yet small compensation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.